Room 237

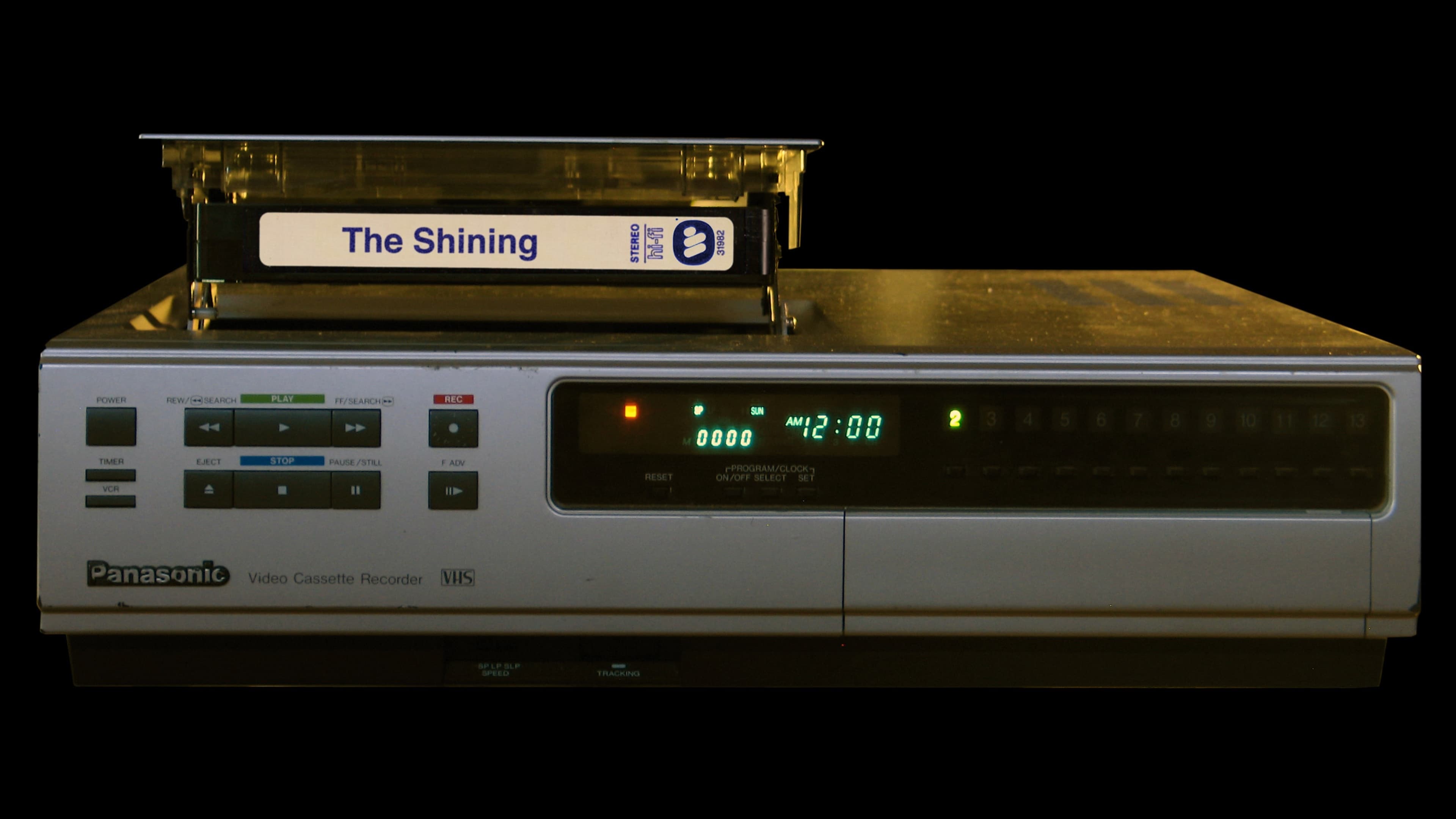

A subjective documentary that explores various theories about hidden meanings in Stanley Kubrick's classic film The Shining. Five very different points of view are illuminated through voice over, film clips, animation and dramatic reenactments.

Gareth Senior@gareth53

An intruiging documentary. If you've loved & watched "The Shining" many, many times, this doc will still show you things you never noticed before.

The premise is that different theories about The Shining are examined. All of them start with an idea triggered by a single shot, but most fall apart as the originator attempts to expand and prove their theory. In the end, most of the theorists reveal themselves to be hilariously lost in the film and their reading of it.

Stanley Kubrick always stated that he wanted the film to have an unsettling affect on the viewer. This documentary proves that he succeeded. In the end "Room 237" is a piece that celebrates Kubrick's directorial brilliance and is a loving analysis of one of his best films.

LastCaress1972@LastCaress1972

"At the end of The Shining, he's reduced to a screaming ape, just like in the beginning of 2001 there are screaming apes." - John Fell Ryan

Astonishingly, the above statement, as bizarre, irrelevant and as bereft of any further analysis as it is (and I haven't taken it out of context; there really IS no further analysis or conclusion mined from that sentence), is possibly the sanest, most rational sentence uttered in Room 237, a documentary film by Rodney Asher lending a platform to some of the whackier interpretations of Stanley Kubrick's terrifying but relatively straightforward adaptation of Stephen King's classic novel, The Shining.

Essentially: The visuals of Room 237 are made up mostly of excerpts from The Shining (but also from other movies, mostly from Stanley Kubrick's or Jack Nicholson's catalogues), either slowed down, sped up, repeated, screen-split, run backwards, overlayed upon itself or augmented with arrows, directional bars or other highlighting/orientation tools in order to assist the points being made at the time on the audio by any one of five contributors, all of whom appear via voiceover only.

Bill Blakemore - a hugely-respected news reporter - is first off of the high board with his assertion that the movie is allegorical of the white man's slaughter of the Native Americans. Because of the hoary old trope that The Overlook of the movie was built on an old Indian burial ground, you see. And that there are pictures of Native Americans or examples of Native American art and culture all over the hotel. The concept that the hotel happens to have a Native American theme, hence the paraphernalia, seems to have passed him by. What HASN'T passed him by is the tin of baking powder in the dry goods storeroom illustrating an American Indian Chief, the appearance of which signifies a "good" thing or a "bad" thing depending on how front-facing the label is in any given scene, or the fact that the elevator doors are shut when the blood pours out of the lift shaft, which is a clear allegory to how white men can't/won't "open up" (Eh? Eh? See what he's done there? Eh?) to the slaughter of the tribes. That axe? Why, that was the axe that the Europeans used to cut a swathe through the Americas, of course! Mind you, our next man up - Geoffrey Cocks, an author specializing in Nazi Germany and of cinematic allegory to the Holocaust; have a guess where HE'S going with his theories - sees the axe scene, in conjunction with Nicholson's line "Little pigs, little pigs, let me come in. [Silence and a pause] Not by the hair of your chiny-chin-chins? Then I'll huff, and I'll puff, and I'll blow your house in" as a clear nod not simply to the well-known fairy tale, no, but to Disney's racially unsound 1933 short "The Three Little Pigs" and the wolf's "Jew" disguise at the pig's door. He adds to his broth Jack Torrance's typewriter (German manufacturer) and frequent uses of the number 42 throughout the movie (2x3x7=42, Danny wears a shirt emblazoned with the number 42, etc.). "When you put a German typewriter with the number 42," states Cocks, "You get The Holocaust." Germany, 1942, you see. Okay.

Juli Kearns and the aforementioned John Fell Ryan - he of the tenuous "ape" comparison above - had the more vague theories: Kearns seemed obsessed with mapping out The Overlook, which only really served to highlight some errors in continuity which were no doubt committed for the sake of the shot Stanley wanted, and not factoring in some madwoman dissecting the film frame-by-frame thirty years later. She also had some half-cocked theories on symmetry, and minotaurs. Fell Ryan didn't appear to even have as much as Kearns - he was mainly presenting an absolutely bonkers theory on behalf of another oddball who declined to be in the film; something about how the film needs to be watched both forwards AND backwards at once, with the "backwards" version overlayed on top of the regular film. But besides highlighting a few similarities in other Kubrick films (at a bloody stretch) and saying that "it's interesting" quite a lot, his ideas didn't seem to really go anywhere. Perversely, this lack of true mentalism inadvertandtly made him the most sensible fellow in the picture.

Best of the lot though is Jay Weidner (described on his own website as "an authority on the hermetic and alchemical traditions"). The Shining is to him no less than an implicit confession by Stanley Kubrick, that he staged the moon landings on behalf of NASA. 237 - the titular room number, changed in the movie from 217 in the book - was the number of the soundstage on which the landings were recorded, of course. It's also 237,000 miles to the moon as well, apparently. The speech by Jack to Wendy, on the stairs ("Have you ever had a single moment's thought about my responsibilities? Have you ever thought for a single solitary moment about my responsibilities to my employers?!" etc.) was Kubrick talking to his wife, about his NASA gig. The barely-seen Summer caretaker Bill Watson (in a couple of scenes near the very beginning)? He's a representation of the CIA, keeping silent tabs on the President, represented by Ullman the manager in his unconvincing wig (of course, to Bill Blakemore, Watson is the manifestation of the Native American cowed into submission by the white man. Pick your poison, everybody! We've got all flavours!).

Haven't these people considered that maybe they've just pulled the film so finely to pieces that they've seen behind the curtain, and found every continuity error in the movie? Well, no. Fanning the nutty flames alongside their utter adoration of Kubrick's filmmaking is the perception Kubrick had garnered for himself as someone who did not make mistakes, ever. So, to these people, there ARE no continuity errors or filmic shortcuts; if they've seen it, Stanley MEANT for them to see it. Because of the secret message he was conveying. That chair that was in shot and now isn't, well that's because of [INSERT LOONY THEORY HERE]. Definitely not an honest-to-goodness gaffe, oh no.

So, is the film any good? Oh, it's entertaining, certainly, in a "WTF?!?" way. It's utter bunkum of course from start to finish, but the filmmaker knows that. He doesn't seem in it to poke fun though (his accompanying visuals almost uniformly assist the theories, only dipping into sly, gently humourous subversion occasionally), he just clearly loves to hear an extreme take on familiar source material. We all love a good conspiracy, don't we? And some of us love an absolutely hair-brained one, too.

8/10, recommended for anyone who enjoyed Trekkies, or Superheroes. Or anyone who loves a twisted tale from the grassy knoll.

Oh, and for people who love The Shining, too.

j0ng@j0ng

This is a pretentious film with assertions that are way out in left field. The reason I gave it this score is my love for the original movie itself.