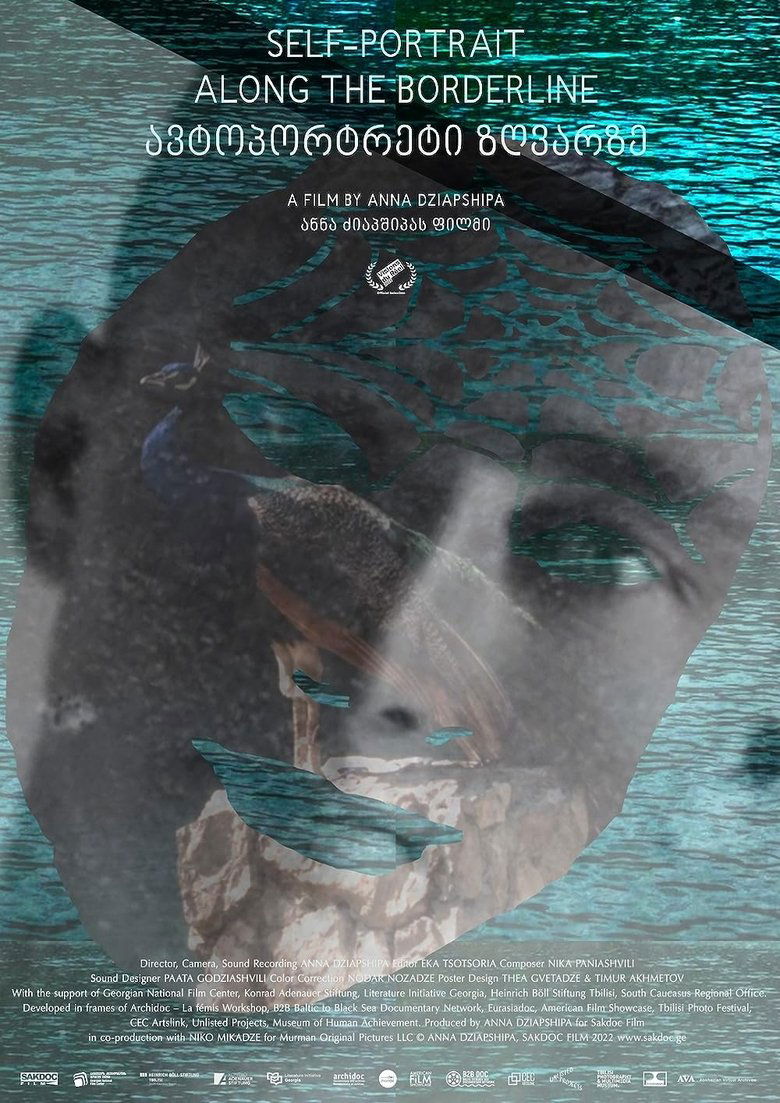

Self-Portrait Along the Borderline

Anna Dziapshipa was born of the union between an Abkhazian man and a Georgian woman. In Self-Portrait Along the Borderline, she skilfully weaves together unique archives and fragments to offer a personal and political biography of Georgia-Abkhazia relations. This vibrant exploration foregrounds a divided identity caught between the margins.

SoilentBxd@SoilentBxd

An abandoned house in Abkhazia, covered with spider webs. It took a lot of effort to get here, since **Anna Dziapshipa** is not allowed to enter the region, as is usual for Georgians. Since Abkhazia declared itself independent in 1994, there has been mutual distrust.

Dziapshipa grew up between the worlds: As the daughter of a Georgian and an Abkhazian, she has been an outsider all her life. In Abkhazia she is considered a Georgian who does not fit in. In Georgian, on the other hand, she is the Abkhazian whose name sounds like an accident (as she tells us later in the cinema). In the film, she gives space to this point by reciting ten versions of "Dziapshipa" with which she was addressed. The correct pronunciation in Georgia is so rare that she can remember each one.

The film is a kind of art project in which Dziapshipa reworks her personal family history and links it to the question of how war shapes society in the long term. Footage of family celebrations and her grandfather Niaz Dziapshipa, who was a well-known soccer player in Tbilisi, are combined in an alienated collage. Thus, her parents' wedding and her own can be seen, depicting her almost threateningly alienated.

In between, there are repeated shots of an older Georgian documentary about spiders. Their spider threads stretch into connections and have something disturbing about them. A vacation documentary from the Soviet era shows Abkhazia as a wonderful vacation destination with sandy beaches and a mild climate. A contrast to the war in the 90s and the smoldering conflict.

In the cinema Krokodil Anna Dziapshipa was a guest and tells about the complicated relations between Georgia and Abkhazia. Thus, she is convinced that times of war always shape a society and its people. Even after decades, anyone who grew up like this as a child or teenager remembers the crises that had to be endured. She pleads for "freeing oneself" from homeland and identity, because in her view it leads to discrimination and displacement.

The Georgian interpreter was also able to contribute a lot and found Dziapshipa's stories visibly interesting. From her point of view, the Georgian side talks about Abkhazia as a country with a beautiful landscape and a vacation feeling. However, they never talk about the people, they simply do not appear. Moreover, they both talk about scratching off the family name on the mailbox in order not to attract unpleasant attention. Dziapshipa says that she is eager to hear feedback about the film from Georgia, which will be shown there in November. She would also like to show it in Abkhazia and travel there. However, she is aware that this can be dangerous, as works about Georgian-Abkhazian relations have a great potential for conflict.